[This article first appeared in the American Bar Association Entertainment & Sports Lawyer, Spring 2017]

There is a fundamental rule of music licensing—if you don’t have a license from the copyright owner, don’t use the music. But in the new new thing of “permissionless innovation,”[3] the “disruptors” want to use the music anyway. Nowhere is this battle more apparent than the newest new new thing—mass filing of “address unknown” compulsory license notices for songs.

You’re probably familiar with U.S. compulsory mechanical licenses[4] for songs mandated by Section 115[5] of the Copyright Act.[6] We think of the compulsory (or “statutory”) license[7] as requiring music users to pay mechanical royalties after serving a “notice of intention” (or “NOI”)[8] on the song copyright owner and complying with other statutory requirements[9]—but it may come as a surprise that some of the biggest contemporary online music users serve millions of NOIs for interactive streaming to both avoid paying statutory royalties and wrap themselves in the liability insulation of the statutory license.[10] And because these users claim they cannot find the address of the song owner, millions of NOIs are served on the Copyright Office and not the song owner.

According to the independent source Rightscorp, [11] a company that has been tracking and indexing all those NOIs as published by the Copyright Office,[12] over 25 million “address unknown” NOIs have been served on the Copyright Office between April 2016 and January 18, 2017, or an average rate of approximately three million per month.

NOI Table

Top Three Services Filing NOIs April, 2016—January 2017[13] and Number of NOIs Per Service

Amazon Digital Services LLC: 19,421,902

Google, Inc.: 4,625,521

Pandora Media, Inc: 1,193,346

But according to a recent story on the subject in Billboard[14]:

"’At this point [June 2016], 500,000 new [songs] are coming online every month [much lower than the reported numerical average to date], and maybe about 400,000 of them are by indie songwriters [which may include covers], many of whom who don’t understand publishing,’ Bill Colitre, vp/general counsel for Music Reports, a key facilitator in helping services to pay publishers, tells Billboard. ‘For the long tail, music publishing data from indie artists often doesn’t exist’ when their music is distributed to digital services.”

Conversely, neither digital retailers, i.e., music users, nor aggregators appear to be able (or perhaps willing) to collect publishing information for new releases or long tail for unknown reasons.[15] Of course, as we will see below, Google has collected publishing information for a decade through its Content ID product, and Music Reports itself sells its Songdex product[16] that contains a significant amount of song data and is widely relied upon by its music user principals.

Whether their motivation is avoiding liability, avoiding royalties, or both, this means that Amazon, Google, Pandora and others[17] pay no statutory royalties on any of the song copyrights in their millions[18] of “address unknown” NOIs until the song copyright owner becomes “identifiable” in the “public records” of the U.S. Copyright Office, a process that arguably defeats Congress’s entire purpose of the NOI in the first place.

This problem will not be solved by maintaining an ownership database in the cloud that would allow users to exploit songs or family pictures until the work is registered.[19] An ownership database does not solve the problem of users who have no penalty for failing to use the database or for willful blindness.[20]

As I think the reader will see, by capitalizing on a perceived loophole in the U.S. Copyright Act, the users may well have gotten themselves absolutely nowhere, the government may have participated in yet another unconstitutional taking,[21] and songwriters, as usual, are left out in the cold to spend precious resources correcting the mistakes of giant multinational corporations.

That’s A Nice Song You Got There—Shame If No One Could Find It

Songwriters have three common reactions to the scale of the “address unknown” NOIs. First, they assume the songs subject to these NOIs must be in the “long tail”. This does not appear to be true, as there clearly are some high value new releases. Yet the industry has handled this “problem” for decades without resorting to mass NOIs.[22]

Songwriters ask how services fail to identify owners when songwriters and their publishers take care to register their songs in the databases readily made available by ASCAP, BMI, GMR and SESAC. [23] Songwriters are surprised to learn that music users need only search the public records of the Copyright Office and not even the databases of the user’s own agent.

But the biggest shock is usually from the sheer number of filings and the realization that these services are getting a free ride from exploiting a loophole.

And because these services do not render accounting statements as I will argue the law clearly requires[24], there is essentially no way for a song copyright owner to know what they are owed in the case of mistake or prospective payment.

Alternatively, if music users unilaterally decide to pay royalties retroactively, it will be even more important that proper statutory accounting statements be rendered for each song. Since users elected the “address unknown” process to serve NOIs on the Copyright Office, it only makes sense that these monthly and annual accounting statements also are served on the Copyright Office.

It is worth noting that the U.S. compulsory license does not accord songwriters an audit right, another loophole in the law that has never been corrected.[25] If these loopholes are combined at scale, then Amazon, Google and Pandora—companies with a combined market capitalization of nearly $1,000,000,000---can exploit millions of songs, pay no royalties, have at least some protection from infringement claims and cannot be audited.

Now that’s a hack. Meet the new boss, worse than the old boss.

Unlike the typical “pending and unmatched” or “black box” distribution, the compulsory license accounting requirements should substantially reduce unmatched exploitations. Since it appears that no statements have been rendered under “address unknown” NOIs for 2016 as of this writing, I will argue that song owners are entitled to send a termination notice to the music service for failure to account regardless of whether the copyright owner is identifiable in the Copyright Office’s public records. I will also argue that if that failure is not lawfully remedied, those purported licenses terminate “automatically”.[26]

How did this mess occur? It all starts with a shard of a statute that arguably was never intended for compulsory licensing.

The Statutory Origins of Mass NOIs

As of April 19, 2016, the U.S. Copyright Office began posting on its website[27] copies of millions of “address unknown” NOIs served on the Copyright Office by Google, Amazon, Pandora, iHeart and other services. These very large music users are taking advantage of two little known and previously little used sections of Section 115 of the 1976 Copyright Act that both define how an NOI is to be sent and also limit when statutory mechanical royalties are payable. Both code sections were enacted decades before the interactive “streaming mechanical” was conceived.

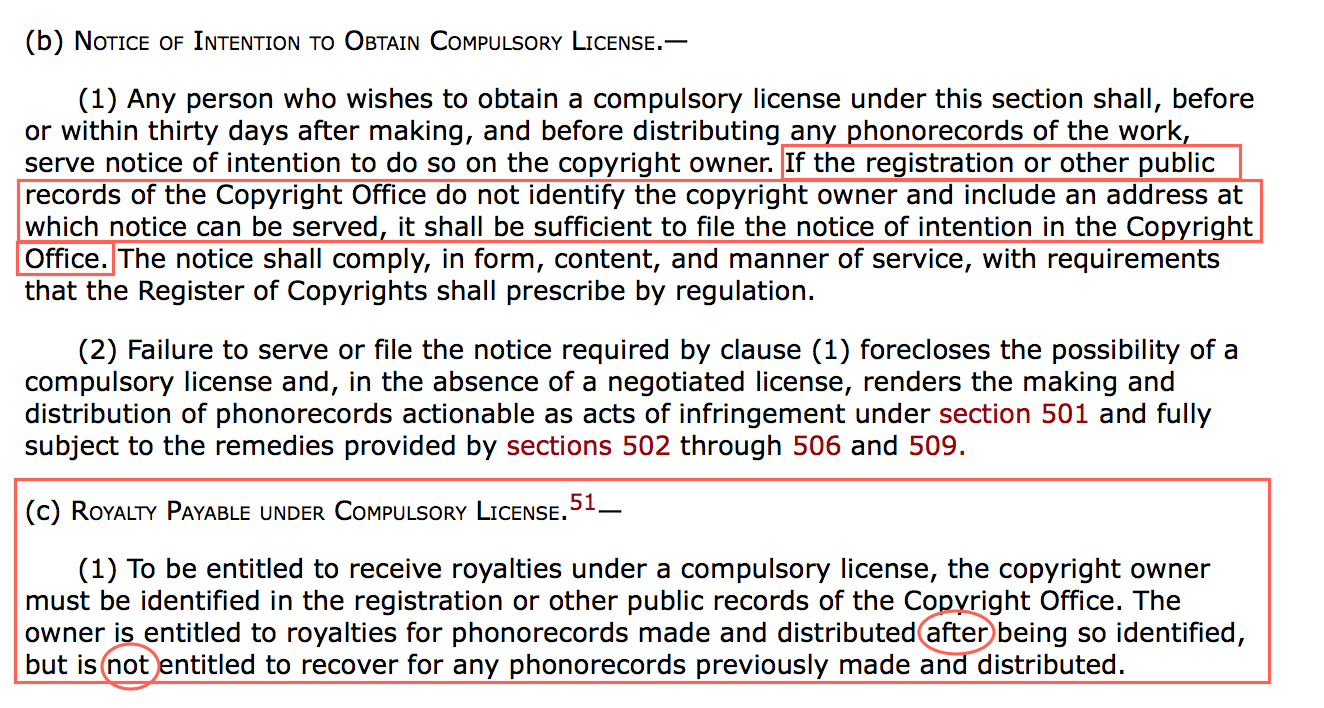

Section 115 (b)(1)[28] (and related regulations[29]) covers how NOIs may be sent to the song copyright owner and is the origin of the “address unknown” NOI:

Any person who wishes to obtain a compulsory license under this section shall, before or within thirty days after making, and before distributing any phonorecords of the work, serve notice of intention to do so on the copyright owner. If the registration or other public records of the Copyright Office do not identify the copyright owner and include an address at which notice can be served, it shall be sufficient to file the notice of intention in the Copyright Office. The notice shall comply, in form, content, and manner of service, with requirements that the Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation.

Section 115 (c)(1)[30] provides when royalties are payable (or not) under an “address unknown” NOI:

To be entitled to receive royalties under a compulsory license, the copyright owner must be identified in the registration or other public records of the Copyright Office. The owner is entitled to royalties for phonorecords made and distributed after being so identified, but is not entitled to recover for any phonorecords previously made and distributed.

The Copyright Act curiously omits any guidance regarding actual knowledge of the music user or its agent regardless of what is in the notoriously incomplete Copyright Office records. For example if the user or agent maintained a voluminous database of song information, can that data simply be ignored?

The Act also does not address knowledge that could reasonably be available to the music user, such as information readily available at no cost in the PRO Databases. It is important to note that music users are simultaneously accounting under blanket licenses to the U.S. performing rights organizations for the performing rights of the same uses of the same songs by the same service. So the PRO Databases are readily available to users.

The Source of the Problem

Users may argue that regardless of what they knew or should have known, if a song copyright owner is not “identifiable” in the “public records” of the Copyright Office,[31] the music user can serve NOIs on the Copyright Office.[32] Once service is effective on properly served “address unknown” NOIs,[33] the music user then is entitled to claim all of the protections from liability for copyright infringement and against audits as a statutory licensee--with the added benefit of avoiding any mechanical royalties.

How will the music user know which NOIs to serve on the Copyright Office? Until music users publicly release that information, we have no way of knowing with certainty.[34]

However, given the patterns in filing that have developed (see NOI table above), one might get the impression that some music users are not checking if the song owner is identifiable anywhere. Instead, it appears at least possible that the users may be simply sending NOIs for all songs they use.

This is troubling because song owners provide multiple ways for licensees to reach them including online databases maintained by the various performing rights organizations such as ASCAP,[35] BMI,[36] Global Music Rights[37] and SESAC[38] that cover over one million songs.[39] But Section (c)(1) requires that users search the database that is the least relevant, the least up to date, the most anachronistic and most difficult to use: The public records of the Copyright Office, which includes the “Public Catalog.”[40]

The Public Catalog has recently taken on a heightened level of importance. One music user responds to address change requests by simply telling the song owner that the music user “now” receives their data from the Copyright Office Public Catalog. This user implies song owner registration is required by Section 115 of the Copyright Act. They also tell the song copyright owner to update their registration with the U.S. Library of Congress—not the Copyright Office.

The clear implication is that all song copyrights must be registered which is simply untrue, however advisable registration may be. As the Copyright Office clearly states, “No publication or registration or other action in the Copyright Office is required to secure copyright.”[41] Registration is not required in order to enjoy copyright protection or the rights of a copyright owner generally other than some litigation-related benefits. As the Copyright Office statement implies, this is old news. [42]

Also note that Congress could easily have required registration in Section 115(c)(1), but did not. Congress contemplated all public records, whether existing in 1978, currently existing[43] or coming into existence in the future. Given that the Copyright Office is subject to Freedom of Information Act requests, “public records” may be very broad indeed.

Since no copyright registration is required, it is not surprising that the copyright owner’s entitlement to receive all benefits of Section 115 is not conditioned on registration[44] including the right to send a termination notice.[45]

Another issue is less obvious—the “data” from the Copyright Office Public Catalog expressly excludes pre-1978 works and is thus inherently unsuitable for purposes of “address unknown” NOIs.

Pre-1978 Public Records

The landing page[46] of the Public Catalog clearly states[47] that pre-1978 records are only available on paper from the Copyright Office.

But note--Section 115 and the accompanying regulations make no such distinction regarding pre-78 works. So if the only effort the music user is making is to search the post-1978 catalog, any purported entitlement to an address unknown NOI for a pre-78 song may well fail.

Setting aside the international treaty implications[48] and the potential lack of pre-78 works in the Public Catalog, it is unlikely if not impossible for a pre-78 song owner to be found in the digitized Copyright Office records. There is no method[49] for copyright owners to “update” or even initially record their contact information unless they either record a document listing all their registered works by title and registration number, or they file a supplementary registration to amend an already completed registration—which is costly.

Which means the song owner must have already registered the works concerned, which is not required in order to enjoy the rights of a copyright owner.

Line of Least Resistance Leads Them On[50]

But why would music users point song owners at the Library of Congress? Perhaps because the Library of Congress sells an electronic database of the post-1978 Copyright Office registration and recordation records. If you can find the link[51] to purchase these databases on the Library of Congress website you are a better researcher than I (or the reference desk at the Library of Congress which couldn’t find it either).

The Library sells two databases that I found: The “Retrospective: 1978-2014” for $50,225 and the “2015 Subscription” for $28,700. These LOC Databases may be the reference data upon which the “address unknown” mass NOI filings are based. These LOC Databases might explain why at least one music user is pointing song copyright owners to the Library of Congress to update their contact information.

Music users (or perhaps their agents) who can afford to purchase these LOC Databases probably could also afford to hire a copyright research service to examine the pre-78 card catalog.[52] But as of this writing, it appears that at least some pre-78 songs may be missed.

While we do not know with certainty how the services or their agents conduct research, we can extrapolate how a list might be compiled.

How Are Song Titles Determined for Mass NOIs?

The process could be as simple as users asking their agent what information is in their agent’s databases, i.e., information of which agent or principal would have actual knowledge. If that is the method used by all music users, then the number of unknown titles should be relatively constant across services and it appears not to be as reflected in the NOI table above.

It may be the case that a user ingests the sound recording metadata and utilizes the sound recording title as the song title.

This might explain why “Fragile” performed by Sting becomes “Fragile (Live)” in Google’s mass NOI filing. If the music user then looks for a song title of “Fragile (Live)” in the public records of the Copyright Office, that title is unlikely ever to be found because the song was registered as “Fragile.”

Given the obscurity-in-plain-sight surrounding mass NOI filings, it is safe to say that unless the song copyright owner is extraordinarily alert and has the computing power to decompress very large NOI files posted on the Copyright Office website, she may never know that her song is being commercially exploited royalty-free.

That’s right—users get all of the benefits[53] and none of the burdens, thanks largely to a haystack of the users own creation.

Building a Haystack of Needles

Sifting through millions of NOIs for your songs is a labor of Hercules for the independent songwriter and even for an indie publisher. Amazon, Google, Pandora and iHeart, among others—but notably, not Apple so far--have built a haystack of needles worthy of the Augean stables. Rightscorp is developing[54] a searchable and indexed database that will allow songwriters to search the mass NOI filings, as may others, but neither the Library of Congress nor the Copyright Office provide any simple way for songwriters to conduct that search as of this writing.

Crucially, it is important that any searchable database come from an independent source as the process is fraught with obvious moral hazard. Neither the services filing the mass NOIs nor their agents should be providing search functions to songwriters as this really would be like asking the fox to file an after action report for the fox’s attack on the chicken coop.

Rendering Statements of Account

It seems improbable that users filed tens of millions of NOIs free of errors. Even a 1% error rate is 250,000 improper NOIs. What is clearer is that no monthly or annual statements of account[55] have been rendered to date and for that reason alone any purported license based on an “address unknown” NOI may be subject to statutory termination.[56] Even if no royalty is payable or only payable prospectively from an unknown time, the statutory obligation to render statements crucially still applies to music users. How will the songwriter ever know what royalties are payable otherwise? This is likely why Congress did not distinguish accounting obligations for “address unknown” NOIs from “known known” NOIs.

Since these statutory users chose to serve NOIs on the Copyright Office, those users have nowhere else to send the required statements but to the same place they sent their NOIs—the Copyright Office. This would be entirely reasonable and consistent with the longstanding requirements that statements be sent to the same address as the NOI.

It is also important to note that the “identification” requirement only applies to NOIs and not to the song copyright owner’s right to terminate the statutory license for failure to account. Note that the termination right is not for failing to render statements to the copyright owner who the music user has decided they cannot identify, but rather for failing to render statements[57] to the Copyright Office that the music user has decided they can identify. This is not a question of having rendered the required statements (and certifications) to the wrong person; in this case, the statements have not been rendered at all.

I would argue that music users ought to serve the lawfully required accounting statements on the Copyright Office because the music user chose to avail themselves of the benefits of Section (c)(1). Allowing the music user to avoid complying with the lawful accounting requirements in addition to avoiding payment does not have a statutory basis and arguably seems clearly outside the intention of Congress.

Indeed, if the Library of Congress fails to require these accountings for millions of NOIs, valuable property rights of potentially hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of the world’s songwriters may be foreclosed.

Eyesight to the Willfully Blind

Note that Section 115 does not address what happens if the music user (or its agent) in fact knows the identity of the song copyright owner at the time of serving the “address unknown” NOI.

Actual knowledge is particularly relevant in the case of companies like Google. Google purchased the mechanical rights licensing company Rightsflow for the very reason that Rightsflow’s database provided valuable rights ownership information for Google to use in its business.[58] Google has also operated its Content ID platform on YouTube[59] for many years through which Google collected vast amounts of song ownership information directly from and at great transaction cost to rights owners. It is difficult to understand how Google in particular does not have actual knowledge of the contact information of millions of song copyright owners to whom it sends statements and payments for other services under other licenses.

Actual knowledge is also relevant in the case of Music Reports, Inc., that apparently is the agent[60] that many of these statutory license users evidently engaged to administer the mass NOI filings. Music Reports not only has developed and marketed its “Songdex” product based on the millions of song owners it can identify, but also has applied for a patent[61] for its mechanical royalty licensing business process. Music user principals of MRI would seem to have access to a vast database of highly reliable song ownership knowledge from a highly credible agent.

Yet it seems implausible and inconsistent with other statutory provisions of the Copyright Act[62] that Congress intended to protect music users who have actual knowledge of the identity of a song owner.[63]

But how will a songwriter even know if their song is implicated?

Which Songs Are Affected?

As noted above, “long tail” deep catalog and new releases seem likely to be affected by “address unknown” NOIs, albeit for different reasons. Deep catalog may be affected because no one registered the song titles or the works were registered before 1978 and the music user did not research the ownership in the paper Copyright Office public records.

New releases may be implicated because the Copyright Office itself has yet to process the registration—and I will discuss the Library of Congress’s limitation on “cataloged registrations” below. Presumably, a filed but yet to be conformed copyright registration would also not be “cataloged”. The Copyright Office acknowledges on its copyright registration portal that the processing time for e-filings is six to ten months, and for paper filings ten to 15 months.[64] This loophole would thus destroy the songwriter’s peak earning power on new releases.

How Mass NOIs Could Be Misidentified

The LOC Database suggests some reasons for potential mismatches:

The only information file available which contains such copyright information as author, title, copyright claimant name, and registration number. Represents cataloged registrations and relevant documents entered into the U.S. Copyright Office database since 1978.[65]

It appears that not all registrations are cataloged and not all documents are entered into the LOC Database. Relying solely on the LOC Databases might result in gaps for “address unknown” NOIs.

Because the LOC Database by definition excludes pre-78 works, these excluded works could be another source of error. The plain language of the Copyright Act includes those pre-78 songs for purposes of an “address unknown” service. How pre-78 copyrights are treated in the mass NOI filings is unclear, but it is worth noting that “Surfer Girl” by the Beach Boys is included in one of Google’s filings[66], which is clearly a pre-78 song.

Who is responsible for cross-checking accuracy? Probably no one. The Copyright Office expressly disclaims any responsibility for incorrect NOIs and warns everyone involved that incorrect notices may only be challenged in a court,[67] in this case by whichever songwriter or publisher who is willing to litigate with the biggest corporations in the world.

That actually leaves it to Congress to take a leadership role in reviewing their library, their statute or any misapplication of these rules.

The Copyright Office Address Unknown Posting

The Copyright Offices posts[68] “address unknown” NOIs on a rolling basis. In order for songwriters to know if their songs are in these NOIs they have to wait for the Copyright Office to post the files, decompress them, sort them, and try to find their own songs by searching the resulting massive Excel file—assuming the songwriter has the skill and computing power available. As of this writing there are approximately 150 NOI filings, but each filing can contain tens of thousands of songs titles for which the music user claims the protections of the statutory license.

This process is not realistic and seems inconsistent with the intentions of Congress.

What is to Be Done?

There are a few ways that mass NOIs can be dealt with. As we review each potential course of action, the same themes will recur: Someone in the government needs to take responsibility for verifying these NOIs are filed as required by law, and the “address unknown” NOI process as currently practiced places an unfair burden on songwriters.

1. Recordation Filing: The Copyright Office will likely accept a simultaneous electronic and paper recordation of a certification of a song copyright owner with a list of song titles. The electronic filing should provide immediate notice to music users. This approach is costly, however, and may be ill suited to individual song copyright owners or independent publishers.

2. Dramatico Musical Works: It appears that the Copyright Office is accepting filings for dramatico-musical works which are not subject to compulsory licenses.[69] (Dramatico-musical works include musicals, for example.) Owners of dramatico-musical works may wish to take ameliorative action to stop the infringing use of their copyrights.

3. Pre-78 Songs: It appears that at least some music users may be ignoring the paper records of the Copyright Office and filing NOIs for song copyrights that may well be identifiable in the pre-78 public records.

4. Improper Filing: However cumbersome, songwriters have a reasonable expectation that the Copyright Office should be able to confirm if the NOIs comply with the statutory requirements. Noncompliant NOIs should be barred.

5. Failure to File and Certify Statements of Account: Regardless of whether royalties are due, music users are arguably required to file monthly and annual statements of account. This is particularly reasonable given the scale of the mass NOI filings, the likelihood of error and the statutory requirements. To my knowledge, no statements of account have been filed as of this writing. This would indicate that all NOIs are subject to termination.

6. Direct Licenses: Based on a sample of songs that I consider likely to be subject to a direct license with a major publisher, it seems possible that “address unknown” NOIs may be getting filed on songs that are directly licensed. Publishers with direct licenses may wish to confirm if they are receiving payments for any directly licensed songs or if users are not paying based on the “address unknown” NOI.

7. Revenue Share Calculations: If songwriters or publishers receive a pro-rata revenue share based on the total number of songs performed during an accounting period, it would be well to determine if non-royalty bearing songs subject to an “address unknown” NOI are being included in the ratio.

Of course, the easiest fix is for the music user to not exploit music without a license from the song owner. That approach has worked well in the past, so perhaps it could work for these music users, too.

[1] Copyright 2017, Christian L. Castle.

[2] Founder, Christian L. Castle, Attorneys, Austin, Texas (www.christiancastle.com).

[3] From Keep the Internet Open by Vinton G. Cerf, Google’s Chief Internet Evangelist, New York Times (May 24, 2012) available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/25/opinion/keep-the-internet-open.html

[4] The statutory mechanical license was established in the United States by the 1909 revision to the Copyright Act, in part to obviate the holding in White-Smith Music Publishing Company v. Apollo Company, 209 U.S. 1 (1908). The Supreme Court held in White-Smith that piano roles were not reproductions protected by the then-current Copyright Act, but also invited the Congress to amend the Copyright Act if the Court’s holding was not welcome: “It may be true that the use of these perforated rolls, in the absence of statutory protection, enables the manufacturers thereof to enjoy the use of musical compositions for which they pay no value. But such considerations properly address themselves to the legislative, and not to the judicial, branch of the government. As the act of Congress now stands we believe it does not include these records as copies or publications of the copyrighted music involved in these cases.” See also Stern v. Rosey, 17 App. DC 562 (D.C. Cir 1901) (holding the “peculiar use” of musical compositions in early wax cylinder phonographs not protected).

[5] 17 U.S.C. § 115.

[6] The Copyright Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-553, 90 Stat. 2541 (Oct. 19, 1976).

[7] A statutory license or “compulsory license” is “a codified licensing scheme whereby copyright owners are required to license their works to a specified class of users at a government-fixed price and under government-set terms and conditions.” Satellite Home Viewer Extension Act: Hearing Before the S. Committee on the Judiciary,108th Cong. (2004) (statement of David O. Carson, General Counsel, U.S. Copyright Office) (May 12, 2004). “[C]ompulsory licensing . . . break[s] from the traditional copyright regime of individual contracts enforced in individual lawsuits.” See Cablevision Sys. Dev. Co. v. Motion Picture Ass’n of Am., Inc., 836 F.2d 599, 608 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (describing limited license for cable operators under 17 U.S.C. § 111). A compulsory license “is a limited exception to the copyright holder’s exclusive right . . . As such, it must be construed narrowly. . . .” Fame Publishing Co. v. Alabama Custom Tape, Inc., 507 F.2d 667, 670 (5th Cir. 1975) (referring to compulsory licenses such as the compulsory mechanical license in the Copyright Act of 1909). Compulsory licenses are generally adopted by Congress only reluctantly, in the face of a marketplace failure. For example, Congress adopted the Section 111 cable compulsory license “to address a market imperfection” due to “transaction costs accompanying the usual scheme of private negotiation. . . .” Cablevision at 602. “Congress’ broad purpose was thus to approximate ideal market conditions more closely . . . the compulsory license would allow the retransmission of signals for which cable systems would not negotiate because of high transaction costs.” Id. at 603.

[8] 17 U.S.C. § 115(b).

[9] 17 U.S.C. § 115(a).

[10] The Copyright Office Copyright and the Music Marketplace report (hereafter “Licensing Study”) notes that many song copyright owners view the entire compulsory licensing system as unfair. Licensing Study at 108, available at https://www.copyright.gov/policy/musiclicensingstudy/copyright-and-the-music-marketplace.pdf (“Many stakeholders are of the view that the section 115 license is unfair to copyright owners. As one submission summed it up: ‘The notifications, statements of account, license terms, lack of compliance, lack of audit provisions, lack of accountability, lack of transparency, ‘one size fits all’ royalty rates and inability to effectively enforce the terms of the license demonstrate a complete breakdown in the statutory licensing system from start to finish.’”)

[11] Mass NOI Update: Christopher Sabec and Rightscorp Tackle the Songwriters’ Copyright Office Problem, Music Tech Solutions (January 26, 2017) available at http://musictech.solutions/2017/01/26/mass-noi-update-christopher-sabec-and-rightscorp-tackle-the-copyright-office-problem/ (hereafter, “Sabec Interview”) andhttp://www.rightscorp.com.

[12] Copyright Office Mass NOI filing page https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/115/noi-submissions.html

[13] Source: Rightscorp, Inc.

[14] Christman, Say You Want a Revolution? U.S. Copyright Office Modernizes Key Part of Digital Licensing, Billboard (June 24, 2016) available at http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/7416438/us-copyright-office-music-reports-compulsory-licensing-digital-notice-of-intent (hereafter, “Christman”).

[15] According to panelists at 2016 SXSW, many retailers refuse to collect publishing information, and aggregators do not collect it or collect it sporadically. Castle, Is It Possible for Songwriter Metadata to Be Delivered to Retailers?, MusicTech.Solutions (March 16, 2016) available at https://musictech.solutions/2016/03/16/is-it-possible-for-songwriter-metadata-to-be-delivered-to-retailers/

[16] According to Music Reports, its Songdex product contains “detailed relational data on tens of millions of songs, recordings and their owners, covering virtually all of the commercially significant music in existence”. Available at https://musicreports.com/#songdex

[17] According to Christopher Sabec, CEO of Rightscorp, as of January 27, 2017 his company has determined that the top three mass NOI filers are Amazon Digital Services LLC (19,421,902 NOIs), Google, Inc. (4,625,521) and Pandora Media, Inc. (1,193,346). There is an unknown overlap among these filings and they are not unique.

[18] There is an as yet unknown degree of overlap between the services filing, so the total number does not necessarily mean that there are 25 million different songs involved, but rather 25 million notices served on the Copyright Office.

[19] See, e.g., Samuelson et al, Copyright Principles Project: Directions for Reform, 25 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 1 (2010) at 10.

[20] David Lowery, Getting Copyrights Right, Politico (May 13, 2013) available at http://www.politico.com/story/2013/05/building-a-real-copyright-consensus-091231

[21] See Professor Richard A. Epstein, Takings (1985); Songwriters of North America, Michelle Lewis, Thomas Kelly and Pamela Sheyne v. the Department of Justice, Loretta Lynch and Renata Hesse (U.S.D.C. Dist. Col. 1:16-cv-01830) at 22 (“Plaintiffs’ constitutional claim is based on theories that the 100% Mandate violates plaintiffs’ rights of procedural and substantive due process, and takes their property without compensation.”).

[22] The Copyright Act of 1909, Pub. L. 60-349, 35 Stat. 1075 (March 4, 1909), revised to January 1, 1973, § 1(e).

[23] By comparison, the European Union has developed a series of sector-specific guidelines for reasonably diligent searches for orphan works Memorandum of Understanding for Diligent Search Guidelines for Orphan Works as part of the European Digital Libraries Initiative available at http://www.ifap.ru/ofdocs/rest/rest0001.pdf (hereafter “EU Search Criteria”).

[24] See 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(5) and 37 C.F.R. §§ 210.16 and 210.17.

[25] See Licensing Study supra note 10.

[26] 17 U.S.C. §115(c)(6).

[27] Copyright Office Mass NOI filing page https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/115/noi-submissions.html

[28] 17 U.S.C. §115(b)(1) (emphasis added).

[29] 37 C.F.R. § 201.18(f)(3).

[30] 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(1) (emphasis added).

[31] It is worth noting that the current Section 115(c)(1) appears to have been a compromise for abandoning the old “notice of use” requirement in Section 1(e) of the 1909 revision of the Copyright Act. The “notice of use” was an obligation on the song copyright owner to file a notice in the Copyright Office when the song has had a “first use”. (“[I]t shall be the duty of the copyright owner, if he uses the musical composition himself for the manufacture of parts of instruments serving to reproduce mechanically the musical work, or licenses others to do so, to file notice thereof in the copyright office, and failure to file such notice shall be a complete defense to any suit, action, or proceeding for any infringement of such copyright. “) As noted in the House Report for the 1976 revision of the Copyright Act, “[t]his requirement has resulted in a technical loss of rights in some cases, and serves little or no purpose where the registration and assignment records of the Copyright Office already show the facts of ownership. Section 115(c)(1) therefore drops any formal ‘notice of use’ requirements and merely provides that ‘[the copyright owner must be identified in the records of the Copyright Office] in order to be entitled to receive royalties under a compulsory license’….” Notes of the Committee on the Judiciary, House Report No. 94-1476, Royalty Payable Under Compulsory License. A topic for another day might be the extent to which this trade off of the 1909 “notice of use” for a 1976 “identification” requirement as a precondition for enjoying the rights of a copyright owner violates the Berne Convention’s prohibition on formalities.

[32] 17 U.S.C. §115(b)(1).

[33] 37 C.F.R. § 201.18(g) (“Notices shall be deemed filed as of the date the [Copyright] Office receives both the Notice and the fee, if applicable.”)

[34] But see Christman, “If a direct deal hasn’t been cut with the publisher but the streaming service, or its agent -- often companies like Music Reports Inc., the Harry Fox Agency’s Slingshot operation, and Musicnet -- know all the rights owners of a song, it has to file a notice of intent with those rights owners. If it doesn’t know all the rights owners, the service can search the Copyright Office's database to see if that song and its owners are registered and, if so, can retrieve addresses and issue a notice of intent. If it can’t find the song or the owners, then the service has to file a notice of intent for the compulsory license for that song with the U.S. Copyright Office.”

[35] ASCAP’s ACE Repertory search is available at https://www.ascap.com/repertory

[36] BMI’s BMI Repertoire search is available at http://repertoire.bmi.com/startpage.asp

[37] Global Music Rights search is available from the GMR homepage www.globalmusicrights.com

[38] SESAC’s Repertory search is available at https://www.sesac.com/Repertory/Terms.aspx

[39] Herein the “PRO Databases”.

[40] U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 23, at 1 available at https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ23.pdf: “Together, the copyright card catalog and the online files of the Copyright Office provide an index to copyright registrations in the United States from 1870 to the present. The copyright card catalog contains approximately 45 million cards covering the period 1870 through 1977. Registrations for all works dating from January 1, 1978, to the present are searchable in the online catalog, available at www.copyright.gov/records.”

[41] U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1, at 3.

[42] Berne Accession available at http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/notifications/berne/treaty_berne_121.html

[43] In addition to the registration and recordation records, the Copyright Office maintains the “CO-10 Address File” with the addresses of “[c]opyright claimants whose address has been requested by a member of the public.” 63 F.R. 51609 (Sept. 28, 1998).

[44] 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(5).

[45] 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(6).

[46] http://cocatalog.loc.gov/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?DB=local&PAGE=First

[47] See id. “Works registered prior to 1978 may be found only in the Copyright Public Records Reading Room.”

[48] See, e.g., Denniston, International Copyright Protection: How Does It Work? available at http://www.bradley.com/insights/publications/2012/03/international-copyright-protection-how-does-it-w__ (“The central feature of the Berne Convention is that it prohibits member countries from imposing “formalities” on copyright protection, in the sense that the enjoyment and exercise of copyright cannot be subject to any formality except in the country of origin. For over a hundred years, the United States resisted joining the Berne Union, in part because of the desire to maintain the formalities U.S. law required. In order to be eligible to join the Berne Union, Congress had to amend the Copyright Act to dispose of the many formalities the Act required. Therefore, while the United States Copyright Act can impose a requirement that the owner of a United States work must register the copyright with the Copyright Office before filing an infringement suit in federal court, it cannot impose that same obligation on foreign nationals.”)

[49] Changing Your Address with the Copyright Office, available at https://www.copyright.gov/fls/sl30a.pdf

[50] Isn’t That So written by Jesse Winchester.

[51] “Copyright Cataloging: Monographs, Documents, and Serials (database)” available athttps://www.loc.gov/cds/products/product.php?productID=23 (hereafter “LOC Database”).

[52] Wall Street Journal Editorial Board, A Copyright Coup in Washington (Nov. 2, 2016) available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-copyright-coup-in-washington-1478127088

[53] Licensing Study 108-110.

[54] See Sabec Interview (“[Rightscorp intends] to create a technological solution to this technological problem. We have already created a searchable database and can assist rights holders in determining the extent of their exposure.”)

[55] See 37 C.F.R. § § 210.16 and 210.17.

[56] 17 U.S.C. § 115(c)(6).

[57] See 37 C.F.R. § § 210.16 and 210.17.

[58] Smith, Google Acquires Music Royalty Manager RightsFlow (Wall Street Journal, Dec. 9, 2011).

[59] See How Content ID Works available at https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370?hl=en

[60] We leave aside the degree to which the agent’s knowledge can be imputed to the principals, but the issue seems ripe, fertile and of particular importance given the scale of the mass NOIs. See, e.g., Restatement (Third) of Agency, Section 5.03 (“For purposes of determining a principal’s legal relations with a third party, notice of a fact that an agent knows or has reason to know is imputed to the principal if knowledge of the fact is material to the agent's duties to the principal….”)

[61] U.S. Patent Application No. 20160180481, “Methods And Systems For Identifying Musical Compositions In A Sound Recording And Licensing The Same” (June 23, 2016) available at http://appft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&p=1&u=%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-bool.html&r=1&f=G&l=50&co1=AND&d=PG01&s1=%22Music+reports%22&OS=%22Music+reports%22&RS=%22Music+reports%22

[62] See, e.g., 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)(1)(A)(i) and (ii) ([a service provider entitled to the safe harbor] does not have actual knowledge that the material or an activity using the material on the system or network is infringing; (ii) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent)

[63] See, e.g., EU Search Criteria.

[64] https://www.copyright.gov/registration/

[65] Copyright Cataloging: Monographs, Documents, and Serials (database), description https://www.loc.gov/cds/products/product.php?productID=23

[66] See https://thetrichordist.com/#jp-carousel-19404

[67] 37 C.F.R. § 201.18(g) states (emphasis added): “[T]he Copyright Office does not review Notices for legal sufficiency or interpret the content of any Notice filed with the Copyright Office under this section. Furthermore, the Copyright Office does not screen Notices for errors or discrepancies and it does not generally correspond with a prospective licensee about the sufficiency of a Notice. If any issue (other than an issue related to fees) arises as to whether a Notice filed in the Copyright Office is sufficient as a matter of law under this section, that issue shall be determined not by the Copyright Office, but shall be subject to a determination of legal sufficiency by a court of competent jurisdiction. Prospective licensees are therefore cautioned to review and scrutinize Notices to assure their legal sufficiency before filing them in the Copyright Office.”

[68] Copyright Office Mass NOI filing page https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/115/noi-submissions.html

[69] 17 U.S.C. § 115 (“In the case of nondramatic musical works, the exclusive rights provided by clauses (1) and (3) of section 106, to make and to distribute phonorecords of such works, are subject to compulsory licensing under the conditions specified by this section” emphasis added.)